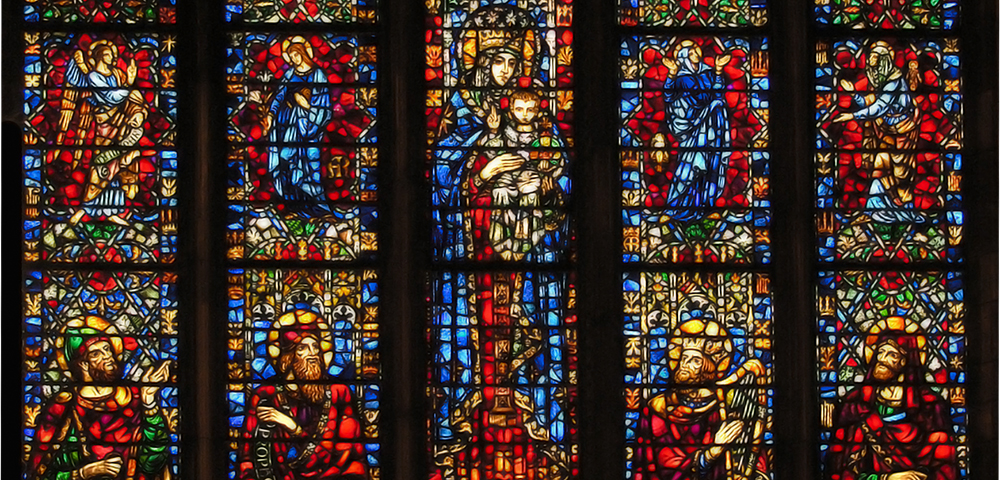

Saint Mary the Virgin with the Christ Child in the stained glass windows of Saint Thomas Church

My soul doth magnify the Lord.

We hear and prayerfully respond to God’s Word

in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Ghost.

My husband works in a building located in the heart of Manhattan’s Times Square. I visited there recently, and as I came out of his building through doors leading onto W. 43rd Street, I noticed, just east and across the street, The Town Hall. Like Carnegie Hall and Radio City Music Hall, The Town Hall is among now landmarked performance spaces built in New York City during the first decades of the twentieth century. Yet, on that day when I visited my husband’s office, I discovered that the original mission of The Town Hall was not as a performance space. As I looked up and beheld the beauty of the Georgian Revival architecture, its brick façade and limestone trim shimmering in the bright, hot sunlight of early afternoon, I noticed these words engraved on a prominent limestone plaque:

The Town Hall

Founded by the League for Political Education

1894-1920

“Ye Shall Know the Truth,

and the Truth Shall Make You Free”

The League for Political Education, I learned later that day, had been established in 1894 by prominent New York City women to advocate for women’s right to vote. Initial meetings of the League met in the home of Eleanor Butler Sanders, a socialite and suffragist after whom the chemistry building at Vasser College is named. The League for Political Education went on, beyond advocating for women’s suffrage, to hold town meetings about various social issues and decided to build a clubhouse to further its mission of providing the general public with political education in support of American democracy. The land at the current site on West 43rd Street was purchased in 1917, the same year in which New York women won the right to vote – a political victory that would provide the momentum for the ratification of the 19th amendment. The Town Hall’s auditorium opened in 1921 and became a central gathering place for political speeches and other approaches to the free exchange of political ideas. The Town Hall would, for example, become the host site of a radio program called America’s Town Meeting of the Air, the nation’s first public-affairs media program, broadcast from 1935 through 1956.

That The Town Hall came into being because of the role and contributions of women in American political education is interesting to consider on this Sunday, when we here at Saint Thomas are observing the Feast of Saint Mary the Virgin and, by our prayers and readings, joining in a catholic observance of a centuries-long belief in her Assumption into heavenly glory. The history of the Town Hall is interesting, because Blessed Mary herself was arguably involved in political education and advocacy in her own day.

What I wish to convey to you today is that the catholic dogma of her Assumption into Heaven might be evidence for her Blessed Mary’s role and contribution within the political landscape.

Our Gospel text, from the first chapter of Luke’s Gospel, tells the story of Blessed Mary’s visitation to her older cousin Elizabeth just after the Angel Gabriel has announced to Mary that, by the power of God’s Holy Spirit, she will bear God’s own Son, Jesus. Elizabeth’s greeting upon Mary’s arrival confirms for Mary that the child within her womb will indeed be the Son of the Most High and the long-awaited Savior. Mary then bursts into words we have come to know as the Song of Mary, the Magnificat:

My soul doth magnify the Lord.

Mary’s song is widely known throughout Christianity, in part because it has been prayed, for centuries, as a canticle of the Divine Office, the daily prayer liturgies of the Church. Here at Saint Thomas, choirs sing the Magnificat during the service of Evensong.

Many in the Church cherish the Magnificat simply for the beauty of its language, perhaps most especially in the Elizabethan and Jacobean English. This past weekend, I attended an outdoor performance in Hyde Park, New York of William Shakespeare’s comedy The Merry Wives of Windsor, and I was surprised and delighted to hear the character SIR HUGH EVANS, a Welsh Parson, caution another character who wrongly believes he has been made a cuckold, saying: “Master Ford, you must pray, and not follow the imaginations of your own heart….” My own heart stirred as I heard these words, wondering whether Shakespeare’s poetic gift influenced the translation of Mary’s Song during the creation of the King James Holy Writ [1]:

He hath shewed strength with his arm;

he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts.

Whatever translation we pray, we Christians cherish the linguistic beauty of Mary’s Song, even as we hold fast to the assurance therein, too, of God’s mercy towards God’s people.

Yet we must also understand that the Magnificat is a significant and radical political statement, a commentary on Mary’s sinful world as it was and an expression of her thanksgiving for the activity of God, through Jesus Christ, in bringing about a new, forgiven, and just world order. The societal reversals about which Mary sings in the Magnificat are stunning:

He hath put down the mighty from their seats,

and exalted them of low degree.

He hath filled the hungry with good things;

and the rich he hath sent empty away.

By her Magnificat, Mary becomes a figure within the stream of great Hebrew prophets in the Bible. The prophets, in each of their days, were socio-religious critics, political figures who called out social injustices. The great prophets of the Hebrew tradition severely rebuked the leaders of Israel and Judah when the people strayed from the commandments to love God and neighbor, and especially when the religious-economic order oppressed the poor, the outcast, and the marginalized.

This summer, congregations across the Episcopal Church have been hearing texts from the writings of the Hebrew prophets who called their communities into judgment before God and envisioned a new and just way of life together. The Book of Isaiah, which foretells of a young woman giving birth to a Savior, begins with these words of the LORD God:

Your new moons and your appointed festivals

have become a burden to me,

I am weary of bearing them.

Wash yourselves; make yourselves clean;

Cease to do evil, learn to do good;

seek justice, rescue the oppressed,

defend the orphan, plead for the widow.

By her Magnificat, Mary becomes, within the arc of salvation history, a prophetic and political figure like Isaiah, like Amos and Jeremiah, like all the Hebrew prophets who came before her.

Meanwhile, as she sings her song, Mary is also becoming a new mother, who will be responsible for raising her child, Jesus. Was Mary, as a mother, like the women who founded The Town Hall here in New York City, concerned not just about having a political voice herself, but also about political education? Did Mary teach her son Jesus honestly about the social injustices of their own day and impart to him the vision of a better world about which she sang in her Magnificat – a better world which Jesus, by the power of the Holy Spirit, would initiate?

One of my favorite paintings of the Virgin Mary with the baby Jesus is Madonna of the Magnificat by the Italian Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli. Boticelli is best known for his mythological subjects, as in his paintings The Birth of Venus and Primavera. Yet he also painted quite a few depictions of the Madonna and Child, many as tondos, or round paintings. One of these, The Madonna of the Magnificat is in the tradition of a literate Mary – the Blessed Virgin you recognize in the myriads of paintings of the Annunciation in which Mary is reading and praying from a Prayer Book as the Angel Gabriel arrives.

In Boticelli’s painting, Mary can not only read, but also write. The painting portrays her dipping a quill into an inkwell as she writes, on the right-hand page of a book, the opening words of her song: “Magníficat ánima méa Dóminum. The infant Jesus gently touches the arm with which she is writing and, sitting in her lap, gazes up towards her. Meanwhile angels, are placing upon her a gold crown. Art scholars will often say that the Christ Child is dictating the words of the Magnificat to Mary and guiding her hand as she writes. Yet if we can make the imaginative leap that a poor, young peasant girl can read, then perhaps she can also write, and perhaps the initiative in this moment of Boticelli’s painting is hers. Was Mary his mother concerned for Jesus’ political education? Did she teach her son the Magnificat and instill in him her own devotion to the Hebrew prophetic tradition?

In the Christology of Luke’s gospel, Jesus’ mission as an adult is, certainly, a prophetic one. Right after his baptism in the Jordan River and the forty days he spends in the wilderness testing his vocation, Jesus’ first act in his public ministry is the moment in the synagogue of his hometown of Nazareth. Jesus is given a scroll of the prophet Isaiah and reads these words:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me,

because the Lord has anointed me.

He has sent me to preach good news to the poor,

to proclaim release to the prisoners

and recovery of sight to the blind,

to liberate the oppressed.

Then he tells those gathered in the synagogue, “Today, this scripture has been fulfilled.” Jesus cared about the poor, the hungry, the powerless. He journeyed to Jerusalem, come what may, to bring them hope, and possibility, and a better world.

In Luke’s Gospel, Jesus is, like his Mother Mary, a prophetic figure and, therefore, a political one, within the lineage of the Hebrew prophets. The reign of God, about which he will teach and which by his sacrificial life and death he will help to initiate, will be marked by social justice. Luke’s Jesus will especially challenge the great societal divide in the biblical world between the rich and the poor.

We know how Jesus died, and in Luke’s Gospel, the Cross happens in part because of Jesus’ courageous willingness to confront the ways in which Jewish society was straying from God’s commandment to love God and neighbor.

We do not know, however, how Mary died or even whether she died. Holy Scripture is silent about this, as are various extra-biblical texts from early Christianity. In time, Christians, in their devotion to the Blessed Virgin, began to believe in the Assumption of Mary – the idea that, when the course of Mary’s earthly life was finished, God took up her body and soul into the glory of heaven. In 1950, Pope Pius XII proclaimed and defined this belief in the Assumption of Mary as Christian dogma.

Importantly, this faith belief – that Mary did not know the corruption of the tomb and was taken up by God into heaven to become the Queen of Heaven – links Mary, as much as does her Magnificat, to the Hebrew prophetic tradition.

Do you remember, in the biblical story of salvation, who else was taken up God into heaven? It is Elijah, the greatest Hebrew prophet of all, who opposed wickedness and brought revival. At the end of his earthly life, Elijah was taken up into heaven accompanied by chariots of fire. You’ll remember from the story of Jesus’ Transfiguration last Sunday how Moses represents the law, and Elijah, the prophets, the Transfiguration revealing how Jesus, the Beloved Son of God, is come to fulfill both the law and the prophets.

Elijah, the great prophet who stood with Jesus on the mountaintop, was, according to the Bible, taken up into heaven. So too, many Christians believe, was Blessed Mary. Jesus’ place within the stream of the Hebrew prophets comes about through Mary, who arguably is herself as great as the prophet Elijah in preparing the way for Jesus, for she is granted the same privilege as Elijah’s of Assumption into the heavenly realm.

For us, then, in our devotion to Blessed Mary and especially on this Sunday as we honor, with great solemnity and beauty, a Christian faith in her Assumption into Heaven, we may wish to avow her concern for prophetic mission and political education. Further, as we go forth from this worship, seeking to live according to God’s will and good purposes, we may wish ourselves to claim the prophetic vision which Mary held, and which her Son held, a vision of God’s saving activity to bring about a new social order marked by fairness, rightness, and restorative justice.

As a simple example of how Christians today might do this: Today is August 14. If this day were not a Sunday, the Church would be observing the lesser feast of Jonathan Myrick Daniels. He was an Episcopal seminarian and civil rights activist who, in August of 1965, was shot and murdered while shielding a 17-year-old black woman from the violence of a white supremacist. Both Jonathan Daniels and the young woman, Ruby Sales, had been working in Alabama in the non-violent civil rights movement, seeking to integrate public spaces and register Black voters. Daniels had taken a leave from his seminary education in Cambridge, Massachusetts, to pursue this civil rights advocacy. The conviction of his calling to Alabama, he once said, deepened during Evening Prayer as he prayed Mary’s Magnificat:

“ ‘He hath put down the mighty from their seat

and hath exalted the humble and meek.

He hath filled the hungry with good things.’

I knew that I must go to Selma.

The Virgin’s song was to grow more and more dear

to me in the weeks ahead.”

Dear Christian people, Blessed Mary, the Godbearer, and Jesus, God’s Son, advocated for the rights of the poor, the hungry, and the outcast. The founders of The Town Hall advocated for the rights of women to vote. Blessed Jonathan Myrick Daniels advocated for the civil rights of people of color. All were inspired and equipped by the Holy Spirit to proclaim a vision for and to work towards a reign of God on earth as it is in heaven.

In our own day, our souls can magnify the Lord by doing so, too – by building, making larger, magnifying God’s reign on earth, here and now. How might we do so, in honor of Blessed Mary, Queen of Heaven, and Jesus Christ our Savior, and in the power of that same Spirit which came upon them and comes upon us in Baptism? What prophetic commitment might we claim and what political voice might we raise? Whose rights to inclusion, dignity, and well-being in our own day need our godly provision and protection? How might we, like the women who founded The Town Hall, contribute to the political education of families, communities, nation, and world to secure these rights?

Ponder these things.

And most of all, as we take our place within the generations of all the prophets, and within the communion of all the saints, both in heaven and on earth, which will someday be one, how might you and I pursue a prophetic mission, like Mary, with rejoicing and a song of glad thanksgiving to God for filling us with grace and with power?

Sermon Audio

References

| ↑1 | The translation “he hath scattered the proud in the imagination of their hearts” appeared previously in the Geneva Bible, which was the primary Bible of 16th-century English Protestantism, including use by William Shakespeare. |

|---|