Array

(

[0] => 60707

[1] => 60757

)

book: [Array

(

[0] => 60707

)

] (reading_id: 152622)bbook_id: 60707

The bbook_id [60707] is already in the array.

book: [Array ( [0] => 60757 ) ] (reading_id: 73487)

bbook_id: 60757

The bbook_id [60757] is already in the array.

No update needed for sermon_bbooks.

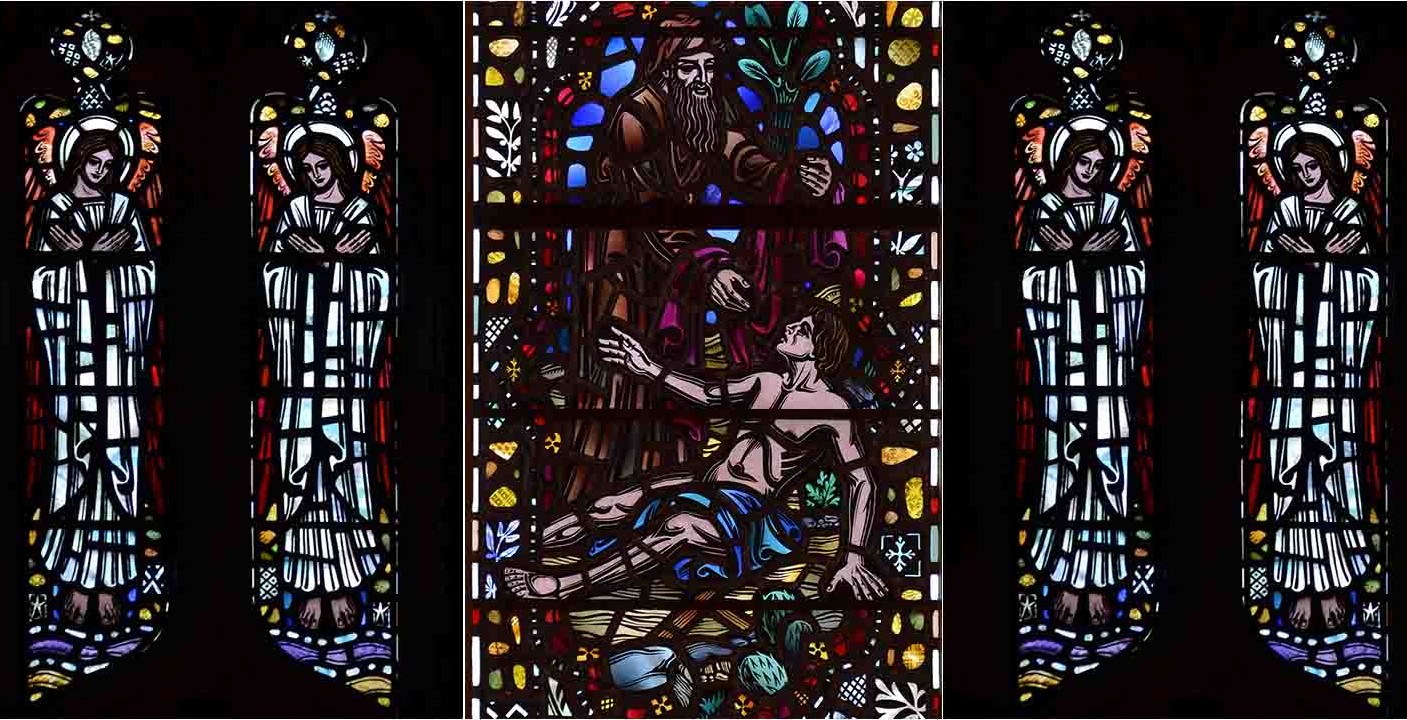

The Good Samaritan depicted in the Goodness Window at Saint Thomas Church

God and the Devil were in a dispute over a broken fence:

God said to the Devil, “You’re gonna have to pay for half.”

The Devil replied, “I ain’t paying anything!”

God said, “You had better pay, or else…”

The Devil replied, “Or else what?”

“If you don’t pay, I’ll sue!” said God.

The devil smiled, and said “And where are you gonna find a lawyer?”

Lawyers have been the but of peoples’ jokes for thousands of years, and in the Gospels Jesus sometimes has a stormy relationship with them. We need to remember that to be a lawyer at the time of Jesus was to understand and interpret the Law, that is, the Torah – those definitive book of the Hebrew Scriptures which not only tell salvation history, but how God’s chosen people were to live in community and in a loving relationship with God. To be a lawyer at the time of Jesus was to bring ones’ faith to bear when interpreting the way that one should conduct ones’ life; to reflect not only on the consequences of peoples’ actions, but also how that affected their relationship with God.

When our pilgrims were in Jerusalem, a few weeks ago, we spent some time at the Western Wall of the Temple complex, where many Jews were saying their morning prayers. A number of small groups were studying the Torah and debating – they were having bible study I guess, like a group of you are doing every Friday with Fr. Schultz. I listened for a while to two charming rabbis who were quietly chatting and looking at their bibles. Noticing my interest, they invited me over for a conversation. We chatted about our common love of the scriptures and how the Hebrew Scriptures are still honored in the Christian Church and, in particular, how the psalms are used every day. They wanted to know about where we came from and they smiled broadly when I said we came from New York. As we were saying our goodbyes, one of them gently leaned over, took my arm, and said to me, “The Creator of the Universe wants salvation for all.” Then, still smiling, he said, “See only good.” That phrase ‘see only good’ stayed with me a lot as we travelled around Israel and the Palestinian Territories; when we saw the wall built around Bethlehem; when we heard the stories at the eye hospital in East Jerusalem.

I wonder if that was the motive behind this particular lawyer’s question. Was he, also, trying to see only good?

Of course, in one respect, the lawyer already knew the answer to the question he was asking Jesus…that’s why he was a lawyer! He knew the scriptures inside out. Like Matthew’s Gospel, the lawyer put the question to Jesus to test him, but here, in Luke’s Gospel, the question is posed differently and respectfully; “Teacher,” the lawyer said, “what must I do to inherit eternal life?” And unlike this same passage in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus turns the question back to the lawyer and says to him, “What is written in the law? What do you read there?” Without hesitation, the lawyer recites the Shema Yisrael – words from Deuteronomy recited twice a day at morning and evening prayers which begins, “Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One. You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength, and with all your mind.” Then, the lawyer adds more words – this time from what we call the Holiness Code of the Book of Leviticus, “and your neighbor as yourself.” To which Jesus simply responds – “You have given the right answer; do this, and you will live.” I like to think of that rabbi at the Western Wall – “See only good.”

The Lawyer then asked what seems to be the real question; “And who is my neighbor?” To which Jesus gave one of the most famous and beloved of parables about the man who falls into robbers’ hands and the Samaritan. (Note that Jesus does not call him the good Samaritan, which makes an assumption about other Samaritans; the description ‘good’ is a title that we have given him, and in so doing we maker an assumption about all other Samaritans).

There are several dilemmas in this parable for the Lawyer. First, the Levite and the Priest knew the Law as much as the Lawyer did; they debated the same kinds of questions about eternal life. But the man is half-dead. Or is he already dead? How would they find out? Only by touching the man; but the man might now be a corpse, and they would become ritually unclean and unable to fulfil their duties in the Temple. For as long as the Law was interpreted as adherence to a set of rules, then the man who fell into the robbers’ hands might as well have been a corpse. The sting in this parable, is the presence of the Samaritan. Most Jews despised Samaritans as not being pure Jews – they were discriminated against on racial and religious grounds. Remember the meeting of Jesus with the Samaritan woman at the well in John’s Gospel? She was feisty! Samaritans were not push-overs; they thought that they were the faithful remnant of Israel, and not those who had their big houses and a Temple in Jerusalem.

The interpretation of the Law as a set of rules and ordinances meant that this Samaritan could never be seen as a neighbor. In fact, he came from the wrong neighborhood. But it doesn’t end there. Just as the priest and the Levite walked on past the man left half-dead, so the Samaritan was moved with compassion when he saw the man. There is no hesitation, he not only bandages the wounds of the poor man, having poured soothing oil on them, he also gave up his own comfortable ride and, probably, his hotel room also for him.

“See only good.”

The Greek word we translate as ‘compassion’ is a very powerful word. It means ‘to suffer with’ but it derives from the Greek word for the great intestine. It is, quite literally, a feeling in the gut – stomach churning; we are talking about an action that moves the whole body. This is not the mind simply thinking that it would be a good or noble thing to help someone in distress (that’s lawyer-speak) the Samaritan was moved within his whole body. Who knows, if this were a true piece of narrative rather than a parable, the Samaritan might have been physically sick on seeing the wretched state of the poor man. This imperative to act within the guts rather than just reasoning with the mind is what separates the values of the lawyer from the values of the kingdom and the need to make a difference and not simply walk by on the other side of the road.

I remember Fr. Kenneth Leech once preaching that the whole point of compassion was sharing together. “Compassion”, he said, is “suffering together and its right at the heart of what it is to be a Christian, and yet many people misunderstand this because they confuse Christianity for niceness, with respectability, with refinement or with good behaviour.” [1]

“See only good.”

When we hear this parable, we think of the Samaritan and his response to that poor unfortunate person and doing good, but the parable has a twist that is easy to miss if we only think of the story as being about doing good to those less fortunate who, nevertheless, are to be seen as our neighbors. For a second time, Jesus turns the question back on the lawyer, “Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?” Let’s stop there; did you notice the subtle shift? Jesus has changed the lawyer’s question. The Lawyer wanted to know who was his neighbor. Politicians, social workers, teachers, and especially the Church like to tell us whom we should count as our neighbor and how we can help them. But Jesus isn’t talking about the man robbed, beaten up and left half-dead. This is not a parable simply about marginalized people or social inclusion. It is not even about being nice to Samaritans. It is far more powerful and has far-reaching consequences: “Which of these three, do you think, was a neighbor to the man who fell into the hands of the robbers?” The question ‘Who is my neighbor?’ is the wrong question. ‘How can you be a neighbor’ is what Jesus is interested in. The Lawyer cannot even say the word ‘Samaritan’ and describes him as ‘the one who showed mercy.’ “Go, and do the same yourself,” said Jesus. In other words, don’t look for who your neighbor might be, go and be a neighbor; don’t pity those less fortunate, don’t just be charitable, be a neighbor yourself. Make relationships that make a difference.

George Caird, the great Congregationalist Theologian said this about the parable: “[Jesus] tells the story of the Good Samaritan, not to answer the question ‘Who is my neighbour?’ but to show that it is the wrong question. The proper question is, ‘To whom can I be a neighbour?’ and the answer is, ‘To anyone whose need constitutes a claim on my love.’ It is neighbourliness, not neighbourhood, that makes a neighbour.” [2]

My dear friends, “See only good.”